Report: ARMS - Reducing Robot Simulation Code by 92%

A concise and intuitive alternative for writing verbose robotics simulation languages, built with browser JavaScript. For more, check out my blog and GitHub.

Project Background

Let’s say you’re designing a robot. This robot will be used to go over rough terrain as part of post-disaster search-and-rescue missions, so it’s important that it be both tall enough to clear uneven ground and stable enough not to topple over on bumps. You want to know: what height and width will offer the optimal combination of ground clearance and stability?

One possible way to find out might be to build several different robots of varying dimensions and test how they perform. But building each physical robot is expensive and time-consuming, not to mention that there might be a lot of feasible height-weight combinations. So you also want to know: is there a way we can test different builds, without the cost of physically building every configuration we want to test?

One of our lab robots taking a selfie during its construction.

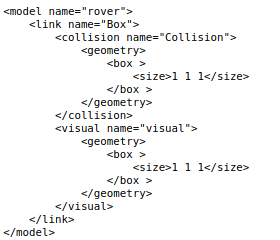

The answer is simulation. By simulating each potential robot design, we can test how it performs without wasting time or materials to physically build it. Simulation has an important place in the robotics field, and a number of tools exist for the simulations of robots: DART, Gazebo, and URDF to name a few. But one common issue with such simulations is that many of these tools require verbose and difficult-to-read input. For instance, let’s look at the XML-based SDFormat used by Gazebo. Consider one of the simplest possible objects - a 1x1x1 cube:

A gray cube on a gray background in Gazebo - so basic, you almost can’t see it.

Below is the SDF code required to create this basic object:

Look at all those tags! I’m getting a headache already. Wouldn’t it be nice if instead we could write something like this:

robot_body = Box{

size = 1 1 1

}

Or, let’s say we want to make many cubes as obstacles for our robot; what if we could define a template called simple_cube to reduce the code even more to something like this:

robot_body = simple_cube(1, 1, 1)

Over the Spring 2021 semester, I worked in Pomona’s Autonomous Robotics and Complex Systems (ARCS) lab to do exactly this: create a simple language that generates robotics simulations in shorter, more legible code and supports useful features like user-defined parameterized templates. Not only would such a language make simulation easier, but it could also be automatically translated into formats for multiple simulation tools. Eventually, we hope to use such functionality to explore aggregating data from multiple simulation engines as a technique for obtaining more realistic simulation results.

I started by working with the SDF language. My goals for the semester were:

- Define a concise and intuitive Autonomous Robot Markup Syntax (ARMS) language that offers similar power to SDF in a condensed, easier-to-use syntax.

- Create a JavaScript parser for ARMS and an application that translates the parsed input to SDF

- Build a simple web interface into which the user can input ARMS, receive an SDF translation, and instantly see a visualization of their scene in-browser.

Development

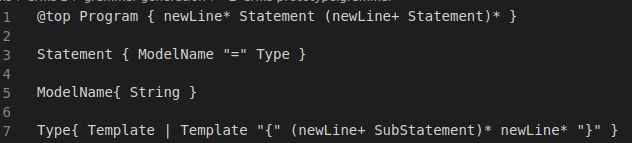

As I started designing ARMS, I surprisingly found myself having flashbacks to Pomona’s Theory of Languages course. Lexing, parsing, context-free grammars, regular expressions: I can’t say that I expected to encounter any of these concepts in a robotics lab. Writing a lexer and parser by hand would be a lot of work, especially since the ARMS language has changed substantially throughout development. Thankfully I found Lezer: a tool that automatically creates a Javascript parser given a user-defined language. The first step was to formally define the ARMS language in a .grammar file:

Part of the ARMS grammar during early development

The language is defined as a context-free grammar, with each rule defined in the format RuleName{ RuleDefinition }. The RuleDefinition can contain RuleNames, tokens, and can use regular expression operators like * (Kleene star), | (or), + (one or more), etc. Tokens are each defined as a regular expression in a @tokens block (the Lezer-generated file will perform both lexing and parsing).

With a grammar in hand, I used Lezer to generate a JavaScript parser for ARMS. I then imported the parser into another JavaScript file and set it to parse user-entered input from a simple HTML interface. One tricky area I ran into is that browser JavaScript currently offers poor support for import statements; to overcome this, I used Webpack to bundle all of my code’s dependencies into a single, self-contained file.

The bundled javascript file for ARMS…holy wall of text!

I then wrote code to evaluate the Lezer-generated parse tree and generate the corresponding SDF code. I gradually built up support for one SDF feature at a time, adding cubes, spheres, joints, and support for variable object scale and position. As I went, the app grew to around 450 lines of JavaScript.

Since text descriptions of 3D objects are error-prone due to being tough to mentally visualize, I decided to add an in-browser visualization of the user’s objects. I accomplished this with ThreeJS, adding code to dynamically generate and render a scene from the user’s ARMS code as its parse tree is evaluated.

Results:

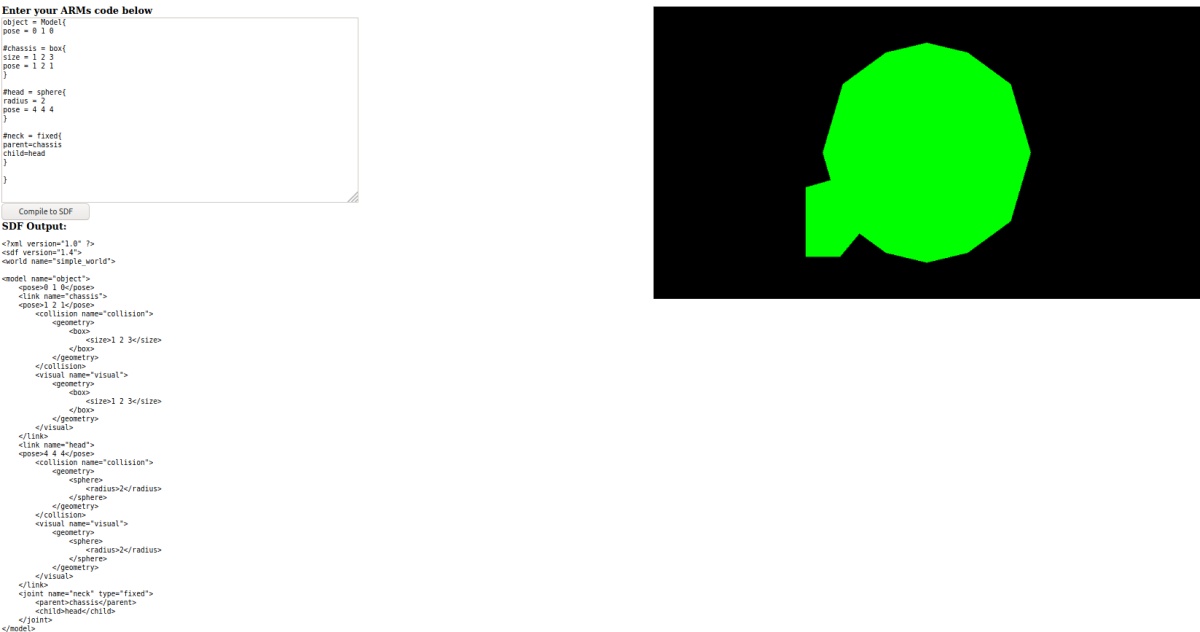

The ARMS app in action

The result is a simple web interface that lets the user enter short and intuitive ARMS code and click “compile”. The app will then output the corresponding, substantially longer SDF code below, along with a visualization of the objects created.

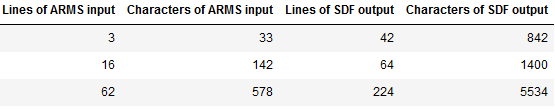

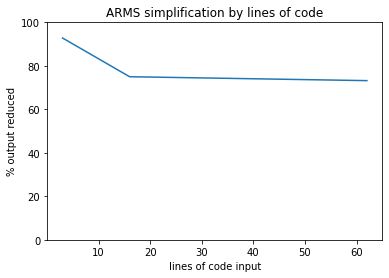

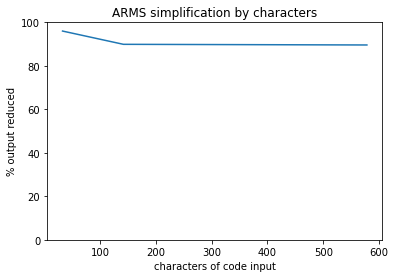

Testing ARMS with inputs of a few different lengths saves the user, on average, 80% by lines of code or 92% by character count. That is to say, using ARMS to generate a SDF simulation requires the user to type 92% fewer characters than writing the SDF by hand themselves.

Three trials of ARMS with various length inputs

Graph of the % of code saved based on input size

The savings are even higher when considered by character count.

The source code for the app can be found on my GitHub. The app can be quickly demoed by downloading “dist/main.js”, “dist/app.html”, and “dist/style.css”. With these three in the same directory, you can simply open the HTML file and the app will run.

The app currently supports the following (see demo above for sample usage):

- All objects are contained in a Model. Top-level statements should be a model definition of the form

ModelName = Model{ Definition }. - A model definition can contain two types of sub-statements: model-wide parameters, defined like

parameter = value, and child objects, defined#objectName = primitive{ parameters} - Currently the only model-wide parameter supported is

pose, setting the model-wide position. - Supported primitive types for objects include

box,sphere, andfixed. boxis a cuboid object that supports the parametersposeand a three-numbersize.sphereis a sphere object that supports the parametersposeandradius.fixedis a fixed joint that requires the parametersparentandchild, both of which should be the objectNames of two other objects in the same model.

Much remains to be done on the app, which I hope to continue work on through the Summer and Fall. Notably, several SDF primitives need to be added; support for user-defined templates is not yet implemented; and stricter type-checking needs to be implemented to catch errors. If you’re interested in reading more on the development process, my full end-of-semester report contains further details including tutorials on each major aspect of development. If you’re working on a similar app or want to contribute to ARMS, feel free to email me with any questions. Thanks for reading!