Report: Autonomous Robot Markup Syntax (ARMS)

This post outlines the development of ARMS (Automated Robotic Markup Syntax) in the Fall 2018 semester at Missouri State University. ARMS is a TOML syntax that is parsed by a Python program called Armature. The purpose of ARMS is to consolidate the specification of robotic parts and joints into one file, while Armature takes that file and outputs the selected target simulation code. For example, currently Armature can output both SDF and C++ code to generate the same robot in both Gazebo and ODE simulation environments respectively.

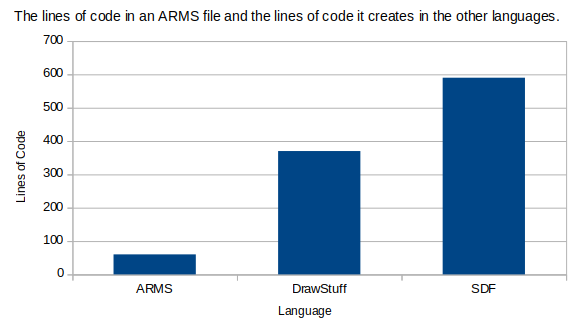

As the figure above illustrates, one file of about 60 lines of ARMS code can output hundreds of lines of working code in other languages. This allows the user to more quickly experiment and tweak the design of a robot, while giving them the source code of that robot to allow them to further fine tune the details to their liking. If the user is working in one simulation environment and it is not working quite how they expect it should, they can run Armature with their ARMS file and instantly have the new environments code without having to write any new code themselves.

This post will discuss the syntax of ARMS that we chose and how we came to that decision. Second, this post will discuss the features of ARMS that were developed in the Fall 2018 semester. Lastly, this post will discuss development that could take place in the future. An example ‘car’ ARMS code is included at the bottom of this post for reference while reading and to use as an example ARMS file.

Syntax of ARMS

The first and most important decision that was made about the design of ARMS was how we would like to write and parse it. It was initially decided that we were going to write our own syntax and parser so we could have maximum control over the syntax. Although, it was quickly found that writing a syntax, parser, and creating functionality all in one semester was not realistic.

It was decided that having a working proof-of-concept was the highest priority to pursue first, so we decided to not write an original language but instead use an existing one that is well defined and supported. After some research, it was decided that TOML was the language that would support our needs and be the fasted to get started with.

The key functionality that made TOML attractive was the concept of an ‘Array of Tables’ which provides us with syntax like this:

#TOML

[[sphere]]

name = "wheel1"

radius = 0.5

relative_position = [1.0, 1.0, 0.0]

[[sphere]]

name = "wheel2"

radius = 0.5

relative_position = [1.0, -1.0, 0.0]

#Equivalent Dictionary

{

"sphere": [

{

"name": "wheel1"

"radius": 0.5

"relative_position": [1.0, 1.0, 0.0]

},

{

"name": "wheel2"

"radius": 0.5

"relative_position": [1.0, -1.0, 0.0]

}

]

}

This code illustrates how TOML creates arrays of dictionaries. These two ‘[[sphere]]’ objects will be stored in one array as dictionaries with the values below them being key-value pairs. This allows Armature to organize all objects of the same type in a convenient manner and handle all of the same type of object simultaneously.

Though, TOML has proven to not be perfect for our needs. There are some use cases where we wish to write ARMS in a certain way that is simply not supported by TOML. For example, while specifying joints in ARMS, you must include a ‘parent’ and ‘child’ attribute to specify which shapes that joint connects. Because the code is written sequentially this results in situations where a joint between two objects could be many lines away from the shape it is actually in relation too. Therefore, we contemplated that idea of using indentation to show the relationship between a parent and child shape. i.e. A child shape would be made the child of another shape by being indented one tab underneath the parent shape. TOML ignores indentation though, so this is impossible with TOML. But, the benefits of creating our own syntax and parser would have to be weighed against the cost of doing so. I would estimate that one entire semester of work would have to be done by someone who has taken the Language and Machines course at MSU to catch that version up to where ARMS is now.

The core of Armature is the Creator interface. A creator is responsible for taking a dictionary created from a parsed ARMS file and outputting it’s generated file. One important feature of the Creators, is that they rely on having objects defined in the dictionary, but it doesn’t know or care about how that dictionary is made. So a potential future parser is completely decoupled from how the Creators create their files. The only limitation is the parser would have to create those dictionary objects in a way that the Creators understand.

Features of ARMS

In the Fall 2018 semester ARMS was developed with very solid features base and is in a good state to be expanded upon. The core of the application revolves around ‘Creators.’ Each target format that ARMS will support will have an associated Creator with it. Armature takes in command line arguments, such as --sdf and --drawstuff and calls the create_file() method of the Creator that can handle that request. Each creator follows a Creator interface so main() does not care how a Creator creates it’s associated file. It just knows it can and sends off the request and a dictionary with all the objects parsed from the ARMS TOML file. This allows future file formats to be easily added by following the patter established and also allow existing Creators to be edited without effecting the other Creators.

The main features that ARMS supports are:

- Spheres

- Boxes

- Revolute Joints

- Ball and Socket Joints

- Prismatic Joints

- Non-collision Groups (ODE only)

- Constants to be used as key words in an ARMS file

- Macros (groups of shapes/joints that can be repeated)

These features were top priority for the ARCS lab and were delivered within the semester and ARMS will be able to be used to further this research now. Through use bugs and other features needed will be found, but this base line of functionality has proven the usefulness of ARMS.

Future Work

The following is ideas on how the project could be further developed.

Original Syntax and Parser:

As discussed in the Syntax section of this post, a new syntax and parser that is created specifically for our needs would be a great addition to this project.

Continued Development of the SDF Creator:

The SDF Creator is a top priority at the time this post was written as it is the format used by Gazebo, which is one of the most popular robotics simulation environments. The SDF creator is probably the best place to start when getting familiar with Armature.

ODE Struct Support:

ODE was initially supported by creating a simulation and displaying it using DrawStuff, a simple graphics library used by ODE to display it’s simulations. To use ODE in Dr. Clark’s own visualizer. A C++ struct object is needed.

SKEL Format Support:

The SKEL file format is an XML format based on SDF and describes objects for DART.

https://dartsim.github.io/skel_file_format.html

Other, more specific things that could be done can be found at the project Trello Board

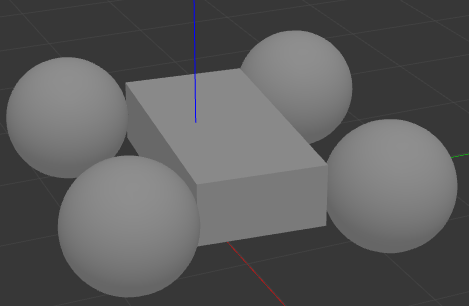

Example model and associated ARMS code

[[model]]

name = "car"

[[constants]]

wheel_radius = 0.5

#Macro Creation

[[macro.wheel_and_axis]]

parent_name = ""

my_name = ""

relative_child_position = []

relative_joint_position = []

joint_axis = []

[[macro.wheel_and_axis.sphere]]

name = "$my_name"

radius = "$wheel_radius"

relative_position = "$relative_child_position"

[[macro.wheel_and_axis.revolute]]

name = "$my_name"

axis = "$joint_axis"

relative_position = "$relative_joint_position"

parent = "$parent_name"

child = "$my_name"

[[box]]

name = "body"

sides = [2.0, 1.0, 0.5]

position = [0, 0, 0]

[[wheel_and_axis]]

parent_name = "body"

my_name = "wheel1"

relative_child_position = [1.0, 1.0, 0.0]

relative_joint_position = [1, 0, 0]

joint_axis = [0, 1, 0]

[[wheel_and_axis]]

parent_name = "body"

my_name = "wheel2"

relative_child_position = [1.0, -1.0, 0.0]

relative_joint_position = [1, 0, 0]

joint_axis = [0, 1, 0]

[[wheel_and_axis]]

parent_name = "body"

my_name = "wheel3"

relative_child_position = [-1.0, -1.0, 0.0]

relative_joint_position = [-1, 0, 0]

joint_axis = [0, 1, 0]

[[wheel_and_axis]]

parent_name = "body"

my_name = "wheel4"

relative_child_position = [-1.0, 1.0, 0.0]

relative_joint_position = [-1, 0, 0]

joint_axis = [0, 1, 0]