Report: Deep Sea Robotics Part 2

Abstract

According to the Smithsonian, the deep sea makes up over 95% of the Earth’s living space with an astonishing variety of organisms. It provides ample opportunities for discoveries in fields of medicine, culinary arts, and energy production. Knowledge of the deep sea helps to predict and prepare for sea-related hazards such as earthquakes and tsunamis, which causes billions of dollars of damage each year. While we continue to explore the deep sea, we have a long way to go before reaching the level of understanding that humans have about the land and sky. Less than 20% of the sea is explored and mapped (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2018). Exploration of the ocean is often difficult due to the high cost, complexity of underwater vehicles, and the limitations of technologies. This study designs a prototype robot with mobility that can withstand deep sea conditions, navigate the water, and collect biological, chemical, physical, geological, and archaeological data using Gazebo Simulator. The final prototype can withstand 200 atmospheres of pressure (2000 meters below the sea surface), navigate with an Xbox 360 controller or the command line, and collect data with pressure sensors, camera, GPS, and magnetometer.

Introduction

The ocean and its understanding is essential to mankind. A better understanding of the ocean could make it possible to regulate climate, better ship products, and improve services like food, medicine, and much more. For the fiscal year of 2020, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) allocated $42 million to Ocean Exploration and Research (NOAA, 2019). In the past, we have relied on sonar imaging to collect data from the sea, due to the cost, complexity of underwater vehicles, and the limitations of technologies available. The most efficient way to explore the deep sea are through remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and automated underwater vehicles (AUVs).

The first step in robot development typically involves simulation. A simulator is a tool developers use to design and prototype robot hardware and software without a physical device. Designs can then be fabricated and transferred to a real-world system. Use of a simulator in early design stages saves both time and cost. For underwater vehicles, simulation prior to actual operations is critical. Missions with underwater vehicles are even more costly and time consuming due to the special environment, the salinity, depth, and movement of the sea. Losing a prototype at sea if communication fails is exactly the scenario that scientists and developers try to avoid. In this study, I create a deep sea robot with consideration of current deep sea robots, different simulation platforms, operating systems, and shapes.

Engineering Goals

This goal of this project is to design a robot that can withstand deep sea conditions and navigate the waters, which can help to make discoveries and better our understanding about the deep sea.

Background and Related Work

With no previous experience in simulating robots, I devoted a month and a half of initial research time to installing, differentiating, and understanding necessary programs; including, Gazebo, the Robot Operating System (ROS), Linux distributions (i.e., Ubuntu), and 3D software. To use these programs, I had to code in XML, C++, and Python.

Gazebo Simulator is an open-source dynamic 3D simulator with the capability to simulate populations of robots in complex indoor and outdoor environments (Gazebo, 2019). Working together with ROS, which provides necessary interfaces for the robot, Gazebo has become a powerful and popular robot simulator for the roboticists. It has been used as the simulation platform for many national and international contests, such as DARPA Subterranean Challenge (2018-2021), Virtual RobotX Competition (2019), and the NASA Space Robotics Challenge (2016-2017).

However, Gazebo and ROS are only compatible on Unix operating systems, and not Microsoft Windows (the operating system on my computer). Thus, I spent time choosing an operating system compatible with both Gazebo and ROS out of MacOS and Linux Distros (Linux Mint and Ubuntu). The biggest difference between Linux Mint and Ubuntu is user interface and support implementations (Devčić, 2016). After experimenting with Linux Mint and Ubuntu, I opted to use Ubuntu 18.04 which proved more efficient to download and run Gazebo. There is also more documentation in the context of robot simulation with Ubuntu.

After setting up my computer, I studied 3D software program that I could use to create meshes that simulate the robot. I ended up using Blender over Maya and 3ds Max, because of its price and compatibility with Ubuntu (Educba, n.d.). Then, came the challenge to design a robot through simulation.

Methods

To develop my aquatic robot, I split the task into two parts: the environment and the robot. After setting up my computer, I devoted the first four months to developing the environment that my robot would reside in, with the help of the Unmanned Underwater Vehicle Simulator (UUV Simulator). Next, I spent another four months developing the actual robot and resolving any issues.

Using the Unmanned Underwater Vehicle (UUV) Simulator

The Unmanned Underwater Vehicle (UUV) Simulator is a package of Gazebo plugins and ROS nodes that facilitate the simulation of underwater vehicles and environments, initially created for the EU ECSEL Project SWARMS (Manhães et al., 2020). My project utilized the UUV simulator to develop the robot and its environment. Although Gazebo has several built in default underwater environments, they are not as sophisticated as the UUV simulator that is appropriate for my research. On the other hand, the UUV Simulator is not very well documented or updated. Some issues exist in the installation and the creation of new vehicles.

Environment

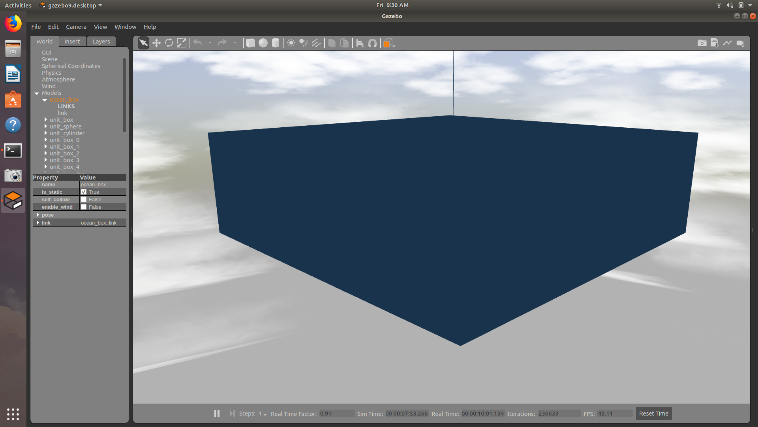

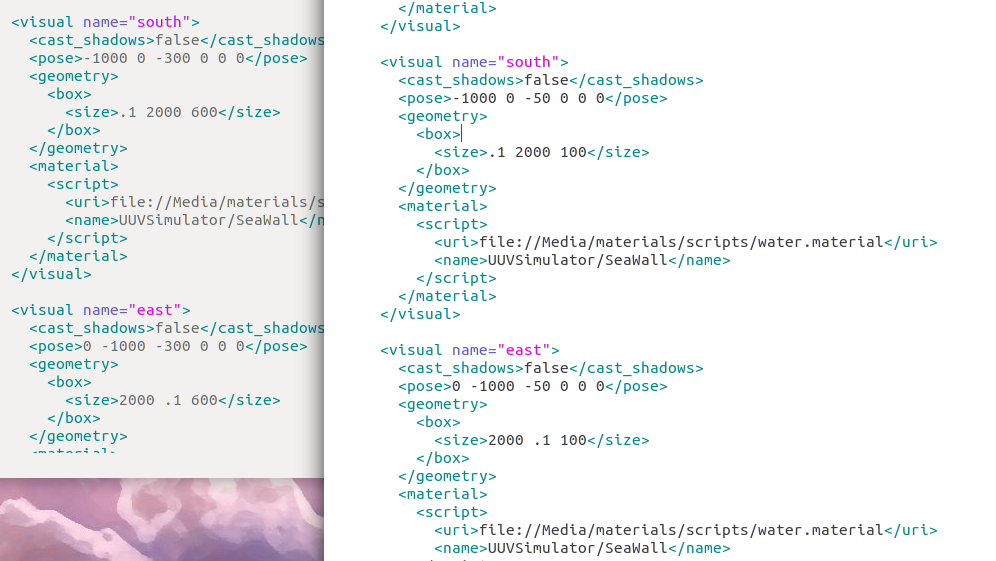

To create a functioning environment for my aquatic robot, I altered, merged, and tested parts of the empty underwater world and the lake environment in the UUV simulator. The empty underwater world is a body of water in a rectangular prism (Figure 1). To consider additional depth that would better suit my aquatic robot, I expanded the pose and collision of each of the “walls” of the sea (Figure 2).

Figure 1: The underwater world zoomed out.

Figure 2: Code of deep-sea environment.

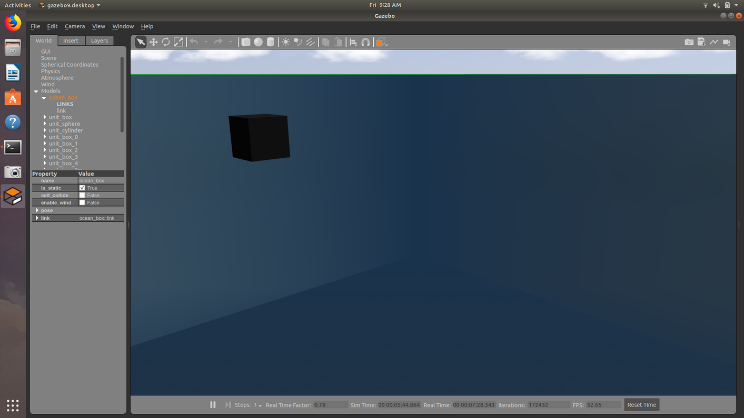

The depth I defined was 2000 meters. The final dimensions are 8000x8000x2000 meters. The underwater world has pressure and density of water. One way that I tested the buoyancy of the simulator was by verifying denser objects sunk (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Cube sinking in sea environment.

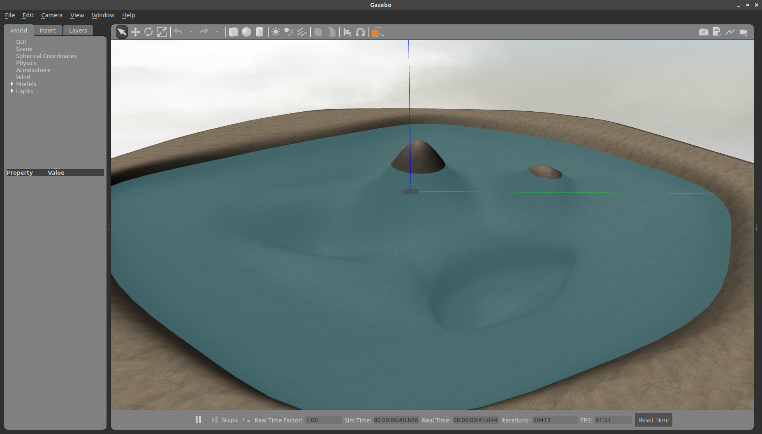

Afterwards, I combined the lake environment (Figure 4) with the empty underwater world environment to build a deep sea environment with varied topography at the sea floor.

Figure 4: The sea floor of the deep sea environment.

Robot

Initial Research

Prior to simulating my aquatic robot and making design choices, I studied how different materials and shapes interact with deep sea pressure, existing deep sea robots, and animal adaptations to the deep sea.

Shapes and Materials

One of the biggest challenges to building a robot underwater, as opposed to land is the difference in pressure. Pressure is defined as the force per unit area. Unlike gas, water does not exert equal pressure on all sides. More pressure is exerted on the bottom of the object than the top. Combined with the descent of an object in water, pressure is constantly changing. For each 10 meters of depth, the pressure increases by one atmosphere.

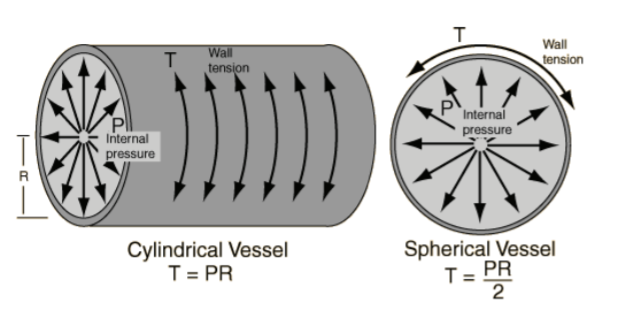

To counteract the forces of pressure on the material, wall tension occurs in the material’s casing. Wall tension is proportional to the radius and the pressure exerted. The most common shapes used for pressure vessels are spheres and cylinders. The cylinder’s wall tension or hoop stress is calculated as:

’’’ \(\sum F_x=0\) \(2 \left(σ_hA\right) -pA_p = 0 = 2\left(σ_h t dy\right) - p 2r dy\) or solving for $σ_h$ \(σ_h = \frac{pr}{t}\) ‘’’

Where $A_p=$ projected area, $d_y=$ incremental length, $t=$ wall thickness, $r=$ inner radius, $p=$ gauge pressure, and $σ_h$ is the hoop stress/wall tension.

The sphere’s calculated wall tension:

’’’ \(\sum F_y=0\) \(σ_hA - pA_e = 0 = σ_a pi \left(r_o^2 - r^2\right) - p pi r^2\) or solving for $σ_a$ \(σ_a = \fract{p pi r^2}{pi \left(r_o^2 - r^2\right)}\) substituting $r_o = r + t$ gives \(σ_a = \fract{p pi r^2}{pi \left(\left(r+t\right)^2 - r^2\right)}= \fract{p pi r^2}{pi \left(r^2 + 2rt + t^2 - r^2\right)}= \fract{p r^2}{pi \left(2rt + t^2\right)} since this is a thin wall with a small t, t^2 is smaller and can be neglected such that after simplication\) \(σ_a = \fract{pr}{2t}\) ‘’’

Where $r_o =$ inner radius and $σ_a$ is the axial stress/wall tension. Both wall tensions are calculated assuming that the object is at equilibrium; the sum of the forces is $0$. The resulting wall tension of a sphere, with a given radius r is two times smaller than that of the cylinder (Bednar, 1981).

Figure 5: Cylindrical and spherical vessel pressure.

Thus, the sphere is the most efficient shape to withstand pressure because of its equal distribution on all sides and its minimal surface area. This makes the sphere a better candidate for pressure vessels. However, due to the high cost of manufacturing a sphere vessel, a cylinder is the more common pressure vessel in current existing studies (Geelhoed, 2016).

Current Deep Sea Robots

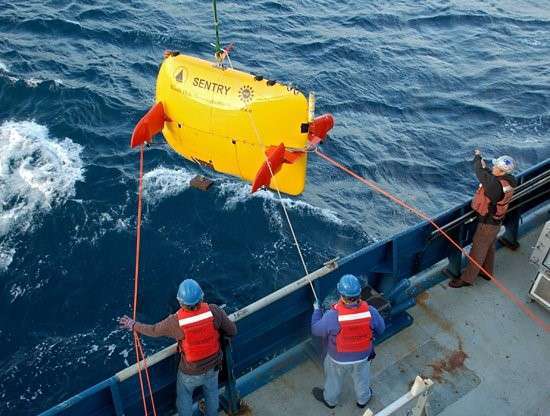

Today, un-manned deep sea robots can be categorized as remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) or autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs). While ROVs must be physically connected to the ship in order for humans to operate, AUV’s are independent, pre-programmed, and free of cords. ROVs are better at collecting samples and manipulations of the sea floor with human manipulation; however, AUVs are more efficient at creating detailed maps and measuring properties of the water with free movement (Chadwick, 2010). Today, there are even ROV/AUV hybrids. Some of the most famous and efficient deep sea vehicles used by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA, n.d.c) include the AUV Sentry (Figure 7), ROV Deep Discoverer (Figure 5), and ROV Hercules (Figure 6). The most common design for ROVs is a prism frame.

Figure 6: ROV Deep Discoverer from NOAA.

Figure 7: ROV Hercules from NOAA.

However, the AUV Sentry has a more streamline design that allows it to ascend, descend, and move through the water quickly.

Figure 8: AUV Sentry from NOAA.

The main purposes of these robots are to collect biological and geological samples, as well as, survey the sea floor with sonar mapping systems.

Deep Sea Animals and their adaptations

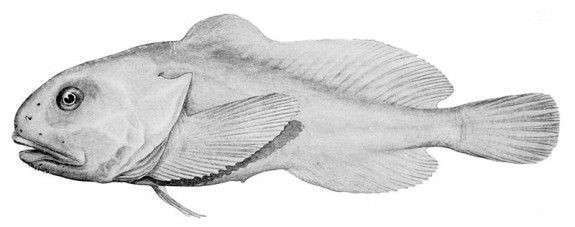

There are many animals with incredible adaptations that can survive the crushing pressure of the deep sea. A few include the blobfish, giant squid, and Cuvier’s beaked whale. Above the sea surface, the blobfish (Figure 8) is often deemed the ugliest creature. But its misshaped, ‘blobby’ appearance is just an example of how drastically deep sea pressure is different from the water at surface. Living over 600 meters below the sea surface, the pressure is 120 times greater. At the surface, the blobfish may be a little floppy; but deep down, in its habitat, the blobfish would be a regular shaped fish (Figure 9) due to high water pressures. Like the blobfish, other deep sea creatures often lack a swim bladder, a gas filled cavity which acts to keep a fish buoyant in the water. This absence means that the creature will not collapse under the extreme pressure (Schultz, 2013). This is also one of the reasons why super-deep sea fish have minimal skeletons and little muscle (Wittenberg et al., 1980). In the context of deep sea vehicles, the optimal robot would contain very little skeleton and no gas-filled cavities too.

Figure 9: Blobfish at sea surface.

Figure 10: Blobfish in its natural habitat.

The giant squid (Figure 10) is an elusive deep sea creature that is very rarely captured on camera. Some adaptions it has to the deep sea include its large eye and lack of bones. Due to the darkness deep underwater, their huge retinas allow them to capture the smallest amount of visible light (Ames, 2019). For a deep sea robot, any pictures or videos, must have its own light source or not use visible light. The giant squid is an invertebrate and lacks bones, very similar to the blobfish’s adaption to the deep sea.

Figure 11: A giant squid.

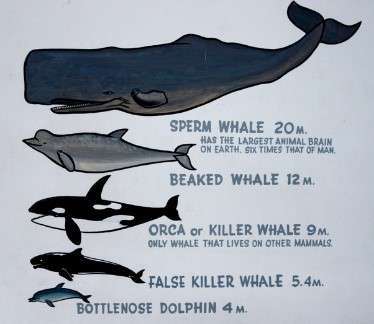

Finally, the Cuvier’s beaked whale can rapidly adjust to the deep sea pressure, diving over 2,000 meters below the sea surface. Unlike other whales and mammals that dive deep beneath the sea, such as the sperm whale, the beaked whale is relatively small (Amos, 2014).

Figure 12: size comparison between sperm whale and beaked whale.

To dive so deep, the whale must store enough oxygen for the lengthy trips and endure the crushing pressure of the deep sea. Beaked whales rely on oxygen to breathe, so they must be able to hold their breath for long periods of time. In an aquatic robot, this is not a problem because robots do not breathe. As the beaked whales descends, their lungs shrink and gasses such as nitrogen in their blood and tissues will be compressed. The theory to how the beaker whale adapts to this scenario is by collapsing its lungs to force air away from the alveoli, which transfers gasses into the blood (Pavid, 2017). For an aquatic robot, this may mean having collapsible parts.

Prototype 1

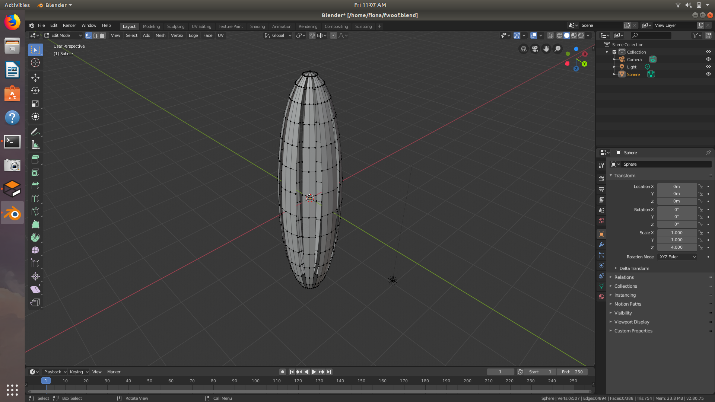

To create my initial model and its meshes, I used Blender, a 3D software program. It took me a while to get comfortable with the controls and build 3-D shapes. While deciding what shape to use, I studied different shapes that comprise manmade underwater vehicles such as submarines, cameras, and more. The first prototype was relatively simple and had no device of movement (Figure 12). The shape at the end became a hemisphere on top of protruding sheets that make an ellipsoid (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Prototype 1 moving down in the deep sea environment.

Figure 14: The ellipsoid of Prototype 1.

I modeled this prototype as an SDF file, which is an XML file type created as part of the Gazebo robot simulator. The SDF file contains objects and/or environments. Some advantages of using the SDF file type are its simplicity and compatibleness with Gazebo Simulator. However, the SDF file type has limitations including the inability to adapt pressure sensors and movement. I moved to the URDF and Xacro file formats for Prototype 2, because there is more documentation on how to use URDF files when modeling robots and it has more capabilities such as adding sensors and movement.

Prototype 2

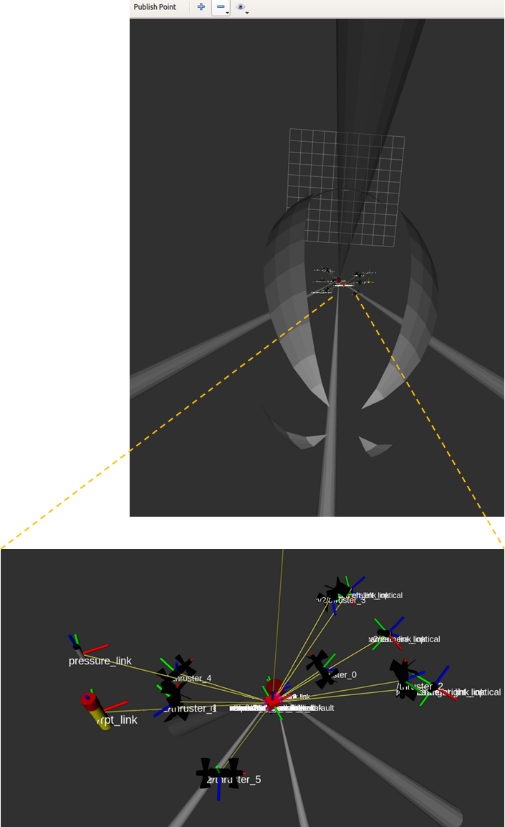

My final product resembles a squid (Figure 14). Unlike Prototype 1, there are fewer sheets/tentacles. The top hemisphere has a radius of 1.44 meters and a width of 0.5 meters. The sheets/tentacles are 4.6 meters in length. All thrusters and sensors are located inside the hemisphere. It uses 5 thrusters to enable its movement. It can be controlled using an Xbox 360 controller and manually controlled through the command line.

Figure 15: Outer appearance of Prototype 2.

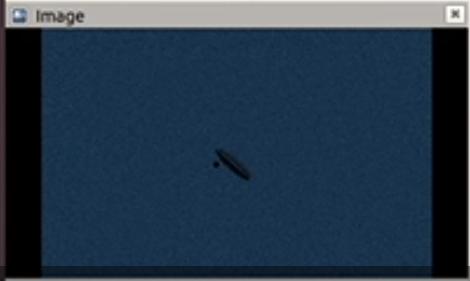

Figure 16: An example of the camera output; the blue is the sea. The two black specks are random objects that I have dropped.

It has several sensors, including a magnetometer to measure magnetic forces, pressure sensors, a camera (Figure 15), sonar, and a GPS (Figure 16). These sensors are all placed underneath the head of the aquatic robot. Please refer to the video for better documentation on how the aquatic robot works.

- Camera allows images and videos.

- Magnometer measures magnetic fields.

- GPS shows coordinates/location of robot.

- Pressure sensor gathers pressure data at the depth of the robot.

- Sonar provides sonar imaging of surroundings.

Figure 17: Sensors inside the head of Prototype 2

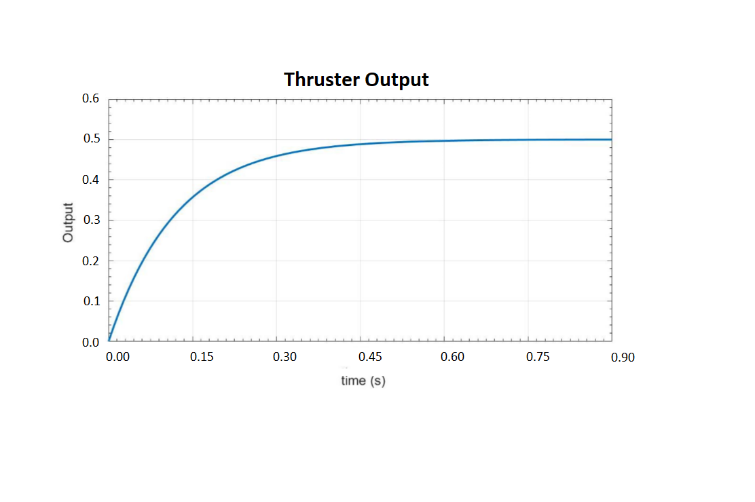

Prototype 2’s thruster type is of first order. Once the thruster reaches its max speed, it stays at that speed, without increasing (Figure 17). The gain that is specified in the launch file determines the limit of speed for the robot.

Figure 18: Thruster output; O=((1-e^(-8x)))/2

I moved the product into a URDF/Xacro format. Unlike the SDF format used in Prototype 1, the Xacro allows for parameters to be passed in. Any changes to the sensors or size of the aquatic robot can be made efficiently. Please watch the video detailing the aquatic robot for more information.

[ ](http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wy12Bud9YRc “”)

](http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wy12Bud9YRc “”)

Conclusion and Future Work

The engineering goals set out at the beginning of this study included designing a robot that can withstand deep sea conditions and navigate the waters. The final prototype, Prototype 2, achieves these goals:

- Prototype 2 does not crush 2000 meters under the sea surface or 200 atmospheres of pressure. I define the deep sea as below 200 meters (Walker, n.d.).

- Prototype 2 can navigate the waters using an Xbox 360 controller and the command line.

- Prototype 2 has pressure sensors, camera, GPS, and a magnetometer that aid in its movement and collecting valuable data.

The deep sea is crucial to our daily lives in unimaginable ways. The deep sea supports fish populations, decreases the impact of carbon emissions, and contain massive reserves of oil, gasses, and minerals used in new technology. Deep-sea environments could lead to new antibiotics and anti-cancer chemicals. Yet, the deep sea is vastly inaccessible and unknown (Smith, 2014). To safely cultivate and not exploit the ocean’s resources, we must understand the deep sea with the help of underwater vehicles like Prototype 2. Prototype 2 is important, as it can help to make discoveries and better our understanding of the deep sea. Although Prototype 2 has reached its initial engineering goals, I can make future advancements including independent navigation, adjustable speeds, more sensors, and expanded robot capabilities.

References

- Aderinola, B. (2019, September 18). ROS in 5 mins – What is Gazebo simulation? Retrieved from https://www.theconstructsim.com/ros-5-mins-028-gazebo-simulation/

- Ames, H. (2019, November 22). The Physical and Behavioral Adaptions of the Giant Squid. Retrieved from https://sciencing.com/physical-behavioral-adaptions-giant-squid-8462698.html

- Amos, J. (2014, March 26). Beaked whale is deep-dive champion. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-26743090

- AUV Sentry. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://ndsf.whoi.edu/sentry/

- Ballard, R. D. (2014, October). Why we must explore the sea. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/why-we-must-explore-sea-180952763/

- Bednar, H.H. (1981). Pressure Vessel Design Handbook.

- The Blobfish: 5 Facts About the Ocean’s Ugliest Mug. (2019, June 25). Retrieved from https://30a.com/worlds-ugliest-fish-blobfish/

- Chadwick, B. (2010, June 25). Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) and Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs. Retrieved from https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/02fire/background/rovs_auvs/rov_auv.html)

- Davies, E. (n.d.). The deepest diving animal is not what you’d expect. Retrieved from https://ourblueplanet.bbcearth.com/blog/?article=the-oceans-deepest-diving-animals

- Devčić, I. I. (2016, September 30). Linux Mint vs Ubuntu: What is the Difference? Retrieved from https://beebom.com/ubuntu-vs-linux-mint-what-is-the-difference/

- Dixon, C. (2015, September 14). Do Humans Have a Future in Deep Sea Exploration? Retrieved from http://Do Humans Have a Future in Deep Sea Exploration?

- Educba. (n.d.). Difference Between Maya vs 3ds Max vs Blender. Retrieved from https://www.educba.com/maya-vs-3ds-max-vs-blender/

- Geelhoed, J. (2016). Materials and shape of underwater structures. Retrieved from https://www.scribd.com/document/439664241/shapes-and-materials-for-underwater-structures-pdf

- Hylton, W. S. (2020, February). History’s Largest Mining Operation Is About to Begin.

- UUV Installation. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://uuvsimulator.github.io/installation/

- UUV Introduction. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://uuvsimulator.github.io/packages/uuv_simulator/intro/

- Kunzig, R. (2001, January 19). The Physics of Deep-sea Animals. Retrieved from https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/the-physics-of-deep-sea-animals

- Manhães, M.M., Scherer, S.A., Voss, M., Douat, L.R., & Rauschenbach, T. (2016). UUV Simulator: A Gazebo-based package for underwater intervention and multi-robot simulation. OCEANS 2016 MTS/IEEE Monterey, 1-8.

- Manhães, M. M. M. (2018, August 29). Enabling the Simulation of Multi-robot underwater missions with Gazebo. Retrieved from https://roscon.ros.org/2018/presentations/ROSCon2018_uuvsimulator.pdf

- MarineBio Conservation Society. (n.d.). Giant Squid. Retrieved from https://marinebio.org/species/giant-squid/architeuthis-dux/

- McKeon, A. (n.d.). Deep-Sea Exploration Will Unveil a Vast, Unexplored World. Retrieved from http://now.northropgrumman.com/deep-sea-exploration-will-unveil-a-vast-unexplored-world

- NOAA. (n.d.). Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Sentry. Retrieved from https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/technology/subs/sentry/sentry.html

- NOAA. (n.d.). Budget Process. Retrieved from https://research.noaa.gov/External-Affairs/Budget

- NOAA. (n.d.). Observation Platforms: Submersibles. Retrieved from https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/technology/subs/subs.html

- Ocean Portal Team. (2018, December 18). The Deep Sea. Retrieved from https://ocean.si.edu/ecosystems/deep-sea/deep-sea

- Palmer, J. (2015, January 15). Secrets of the animals that dive deep into the ocean. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20150115-extreme-divers-defy-explanation

- Pavid, K. (2017, April 27). Secrets of the deepest-diving whales. Retrieved from https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/secrets-of-deep-diving-whales.html

- RJE International. (2017, July 19). What’s the difference between an ROV and an AUV? Retrieved from https://www.rjeint.com/whats-difference-rov-auv/

- Robotic simulation scenarios with Gazebo and ROS. (2015, February 26). Retrieved from https://www.generationrobots.com/blog/en/robotic-simulation-scenarios-with-gazebo-and-ros/

- Schultz, C. (2013, September 13). In Defense of the Blobfish: Why the “World’s Ugliest Animal” Isn’t as Ugly as You Think It Is. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/in-defense-of-the-blobfish-why-the-worlds-ugliest-animal-isnt-as-ugly-as-you-think-it-is-6676336/

- Smith, C. (2014, July 30). Deep Sea Crucial to Our Lives, Study Shows. Retrieved from https://ourworld.unu.edu/en/deep-sea-crucial-to-our-lives-study-shows

- US Department of Commerce, & National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2009, January 1). How much of the ocean have we explored? Retrieved from https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/exploration.html

- Walker, R., & Shank, T. (n.d.). Deep Sea Biology. Retrieved from https://divediscover.whoi.edu/hot-topics/deepsea/

- What is SDFormat. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://sdformat.org/

- Why Gazebo? (n.d.). Retrieved from http://gazebosim.org/

- Wittenberg, J. B., Copeland, D. E., Haedrich, F. R., & Child, J. S. (1980). The swimbladder of deep-sea fish: the swimbladder wall is a lipid-rich barrier to oxygen diffusion. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 60(2), 263-276.

- Wu, F. (2019, December 13). Report: Deep Sea Robotics. Retrieved from https://compusciencing.github.io/report-deep-sea-robotics.html